Central American Food

What follows is the textual content of a speech I had to give in class. It ran deplorably long, because as regular readers know, I love food, and find the anthropology surrounding meals a fascinating topic. So while this seems stilted, if I start expanding it I'll wind up with a book, and I haven't the time!

They say you are what you eat. While that is a terrible cliché, it is true that the food of a culture can tell a story, one that reveals the past influences as well as the needs of the present society. I have been cooking and researching the history of food for more than thirty years, with special interest in Mexican food beginning about 16 years ago. Recently, a friend who is connected to Panama through marriage and time spent living there gave me a recipe and inspired me to learn more about that country’s cuisine.

I want to share more than recipes with you, to take you along on a journey through a land that has been explored, conquered, colonized, and ultimately changed by outsiders from time immemorial but yet we Americans know little about.

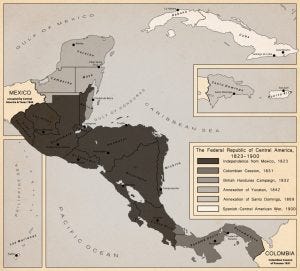

Let me begin with a map, and a little history. We most closely identify Central America – all of Latin America, in fact – with Spain because of the conquistadores and their influences that began in the 16th Century and continue to this day. In his Handbook of Hispanic Culture, Nicolas Kenellow points out that “ironically, due to the successful production of wheat in Latin America, white wheat bread was more available to Latin Americans than to the average citizen in Spain.” The introduction of wheat was what made possible dishes such as the empanada and bunelo, and the commonly found flour tortilla, which has been replacing the older corn tortilla in the role of bread staple.

The introduction to new foods was not a one-way street, on the other hand. The ubiquitous potato, so connected now with German and Irish foods, came originally from the Spanish invasions. The tomato, synonymous with Italian sauces and pizza, was another import from Central and South America. Mexico, the United States, Portugal, all of these countries have left their mark and meals over the centuries. Until 1823, most of Central America was part of Mexico. Portugal, the tiny country with the adventurous explorers, left the bunuelos and the main language spoken in Brazil. The United States has sent food aid, and Coca Cola. (Immink, street art)

Central American food gets less attention than Mexican food for several reasons. In an article in the journal Latino Studies I found a summary: “Not only are many Central Americans forced to adopt a Mexican identity as a strategy of survival in the United States, but many of them perceive themselves as less than Mexicans, that is, belonging to an even more devalued and underrepresented community than that of Mexican immigrants.” (Padilla) And: “Central America as a region has undergone significant changes over the last decades, a period in which general economic growth and political stability were followed by widespread civil war and political violence, to be followed again by a return to some degree of stability,” the Food and Nutrition Bulletin says.

Even Mexican food is far more diverse than most Americans realize. Diana Kennedy in her seminal work on Mexican cuisine, pointed out that the dishes of Sonora, the Yucatán, and Oaxaca have nothing in common, separated by gulfs of geography and culture. Some recipes, such as the bunuelos I mentioned earlier, are found in many countries, but look a little different in each one. .We can find many influences in Central American food today. African influence as outlined in Ntozake Shange’s book If I Can Cook, You Know God Can. Long after Africans struggled with slavery and brutality in Brazil and the Caribbean, she wrote about the parallel between soul food and the foods of the Rio, Lagos, and Vera Cruz.

Yet another example of the cross pollination in the foods is the Panamanian recipe for Corvina al Ajillos I was given to make, it calls for garlic in large quantities. The Spanish for garlic is dientes, literally tooth, which I was tickled to discover, as it’s a fun way to visualize the peeled cloves. Garlic is native to Turkmenistan, and is another European export to the Central American area, one that was embraced whole-heartedly.

I cannot begin to approach the variety you would find in the Central American kitchens and on dinner tables, in the short time I have, but I hope I have left you with an inkling of how the cuisine came to be what it is.

I’d like you to think about your food, the next time you have a chance at a meal: where did it come from? What influences made it possible? And finally, where can I get a taste of Central American food? Ethnic foods need not be a scary prospect, as they can be delicious, and even familiar when looked at through a wider lens.

(author's note: I created a Pinterest board while researching for this, you can find it here, and it has recipes and images which will add to the topic, I think. Also, I did bring empanadas and bunuelos to class with me for my audience to taste. I will put up those recipes soon.)

Bibliography:

8, Andrea González, M. "'Slow Food' quiere tomar fuerza en Costa Rica ('Slow Food' quiere tomar fuerza en Costa Rica)." La Nación (Costa Rica) 23 Oct. 2011: 1. Points of View Reference Center. Web. 16 Apr. 2015.

3, 5 Immink, Maarten D C. "Nutrition, Poverty Alleviation, And Development In Central America And Panama." Food And Nutrition Bulletin 31.1 (2010): 161-172. MEDLINE with Full Text. Web. 16 Apr. 2015.

1, 2 Kenellow, Nicolas. “Handbook of Hispanic Culture – Anthropology” (1995)

6, Kennedy, Diane. “The Cuisines of Mexico” 1972

4, Padilla, Yajaira M. "Sleuthing Central American Identity and History in the New Latino South: Marcos McPeek Villatoro's Home Killings." Latino Studies 6.4 (2008): 376-97. ProQuest. Web. 16 Apr. 2015.

7, Shange, Ntozake. “If I can Cook, You Know God Can” 1998