Myth-Busting: Bacteriophage

#ForScience You can find the first myth-posting here. This one is so egregiously wrong I've corrected it in several places... and it finally exasperated me enough to put the effort into creating this post, so I have one link that I can toss in a comment when I see the meme float across facebook again. Because the bad ones never die.

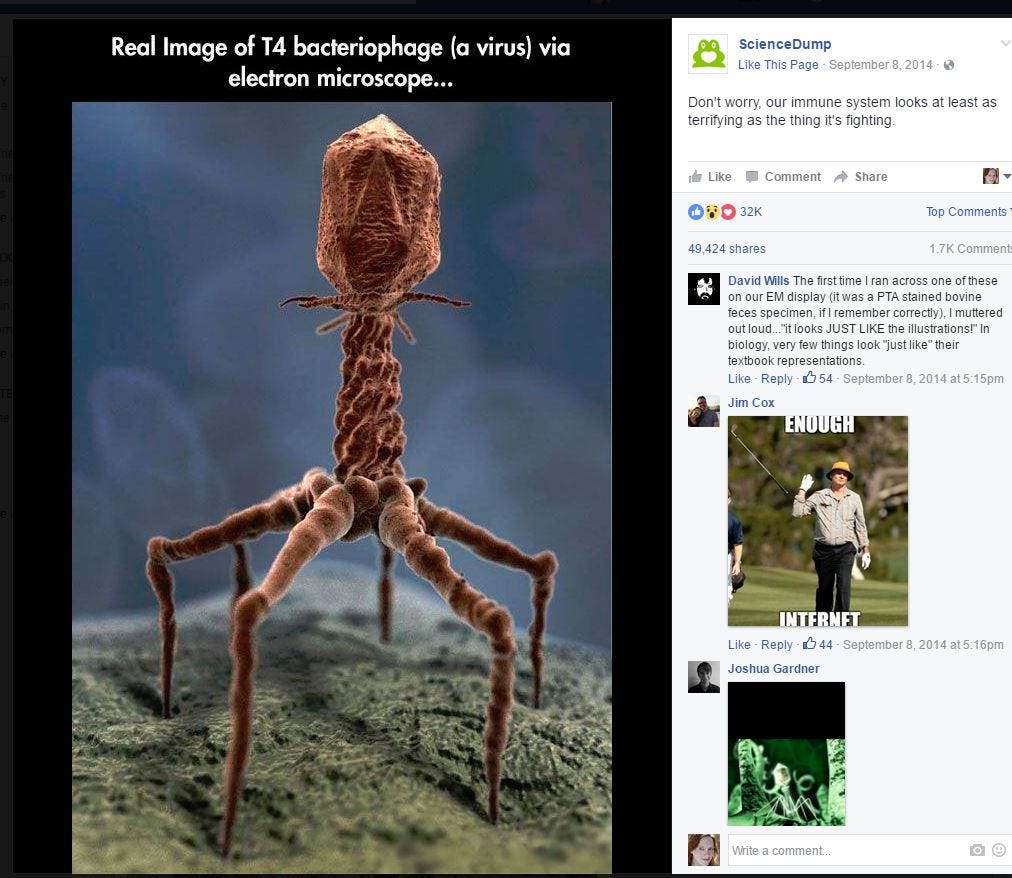

Yes, this is a bacteriophage, and it's pretty darn awesome. Really, who would have expected a structure this beautiful from a technically non-living entity? Yep, that's right. The bacteriophage is not alive. Not really dead, either. Which I suppose is more shiversome than imagining it as attacking our own body cells... except it doesn't do that, either. The caption is implying that our immune system is being attacked by the isocahedral-headed bacteriophage, but anyone who knows a teensy bit about science, and stops to think about it (the latter is most important) will suss out the truth here.

Bacterio - related to bacteria

Phage - eater

So, yeah, this thing is an eater of bacteria. Certainly not human cells, and in fact, it is being studied (and in some places used) as a therapy to help fight human diseases. I recommend the whole article, here, but a short segment will help explain the function of the 'phage.

Bacteriophages or phages are bacterial viruses that invade bacterial cells and, in the case of lytic phages, disrupt bacterial metabolism and cause the bacterium to lyse. The history of bacteriophage discovery has been the subject of lengthy debates, including a controversy over claims for priority. Ernest Hankin, a British bacteriologist, reported in 1896 (21) on the presence of marked antibacterial activity (against Vibrio cholerae) which he observed in the waters of the Ganges and Jumna rivers in India, and he suggested that an unidentified substance (which passed through fine porcelain filters and was heat labile) was responsible for this phenomenon and for limiting the spread of cholera epidemics. Two years later, the Russian bacteriologist Gamaleya observed a similar phenomenon while working with Bacillus subtilis(48), and the observations of several other investigators are also thought to have been related to the bacteriophage phenomenon (72). However, none of these investigators further explored their findings until Frederick Twort, a medically trained bacteriologist from England, reintroduced the subject almost 20 years after Hankin's observation by reporting a similar phenomenon and advancing the hypothesis that it may have been due to, among other possibilities, a virus (70). However, for various reasons—including financial difficulties (68, 70)—Twort did not pursue this finding, and it was another 2 years before bacteriophages were “officially” discovered by Felix d'Herelle, a French-Canadian microbiologist at the Institut Pasteur in Paris.

The discovery or rediscovery of bacteriophages by d'Herelle is frequently associated with an outbreak of severe hemorrhagic dysentery among French troops stationed at Maisons-Laffitte (on the outskirts of Paris) in July-August 1915, although d'Herelle apparently first observed the bacteriophage phenomenon in 1910 while studying microbiologic means of controlling an epizootic of locusts in Mexico. Several soldiers were hospitalized, and d'Herelle was assigned to conduct an investigation of the outbreak. During these studies, he made bacterium-free filtrates of the patients' fecal samples and mixed and incubated them with Shigellastrains isolated from the patients. A portion of the mixtures was inoculated into experimental animals (as part of d'Herelle's studies on developing a vaccine against bacterial dysentery), and a portion was spread on agar medium in order to observe the growth of the bacteria. It was on these agar cultures that d'Herelle observed the appearance of small, clear areas, which he initially called taches, then taches vierges, and, later, plaques(68). D'Herelle's findings were presented during the September 1917 meeting of the Academy of Sciences, and they were subsequently published (18) in the meeting's proceedings. In contrast to Hankin and Twort, d'Herelle had little doubt about the nature of the phenomenon, and he proposed that it was caused by a virus capable of parasitizing bacteria. The name “bacteriophage” was also proposed by d'Herelle, who, according to his recollections (68), decided on this name together with his wife Marie on 18 October 1916—the day before their youngest daughter's birthday (d'Herelle apparently first isolated bacteriophages in the summer of 1916, approximately 1 year after the Maisons-Laffitte outbreak). The name was formed from “bacteria” and “phagein” (to eat or devour, in Greek), and was meant to imply that phages “eat” or “devour” bacteria. Read More...

In short, the bacteriophage is neither part of our own immune system, nor is it a pathogen which our immune system would attack. You're safe... from this virus, anyway.