Writing with Emotion

A snippet of fiction - literally, it was only a couple of hundred words long - passed before my eyes in the last few days, and the discussion over it and what was wrong with it led to this post. I've altered it, somewhat, but left the problems intact for the purposes of discussing the right and wrong way to do this.

Jane has a strange muddled feeling when she awakes hearing a strange noise. Her head has a dull ache and is sore. Slowly opening her weary eyes, she’s unable to make out her surroundings. Slowly her vision starts to clear and she hears a faint tip-tap, tip-tap outside the door.

Something is strange and out of place. There’s a small lamp casting a soft light on a table next to the bed. It’s the only light in the dark room. The bed feels strange to her, it’s softer than her own bed, but it’s comfortable and warm. Suddenly she becomes alarmed. Gazing around the room, she knows this isn’t her bedroom. Guessed what's going on here? This isn't a story, it's a screenplay. Or that's how it reads. We see stage settings, directions, but we aren't really allowed inside the head of the character.

"I was picking up the plant in its miraculously unbroken pot and setting it back atop the windowsill when the phone rang. Since the plant wasn't long for this world from the moment it had entered my house, I sort of patted at the dirt, shoved the pot into a corner of the sill, and rushed off to track down the phone.

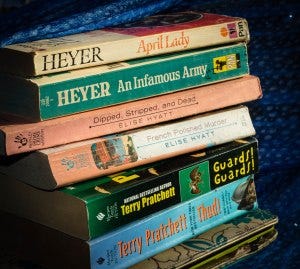

It's not that I put the phone in weird places. It's more like it gets tired of waiting for someone to call and starts roaming around the house, finding ever more inventive places to hide. This time I got it on the third ring because it was only behind the toaster." -- Elise Hyatt, French Polished Murder There, isn't that better? It's a nothing-much passage, but you are let into the world, a character, and in very few words, you have the measure of the book. The stage setting is part of the action - a plant, a toaster, a window - and w know we are in an average home, but one inhabited by a wryly humorous character.

And for a closer comparison, here's an awakening scene. It's rather late in the book, so we already know the character, but as you will see, this does an excellent job of taking you inside the character's head so we feel the wakening acutely.

Vimes opened his eyes. After a while, moving his arm slowly, because of the pain, he found his face and checked that his eyelids were, indeed, open.

What bits of his body weren't aching? He checked. No, there seemed to be none. His ribs were carrying the melody of pain, but knees, elbows, and head were all adding trills and arpeggios. Every time he shifted to ease the agony, it moved somewhere else. His head ached as it someone was hammering on his eyeballs. --Terry Pratchett, Thud Pratchett, of course, is the past master of the colorful metaphor. I always enjoy his work, but even more so, this is a passage that will have you aching in sympathy, it is so vividly realized.

So there you have it, vivid inner realization of external stages set without ever describing them explicitly, and emotions evoked without "suddenly she becomes alarmed."

Don't tell, show!

Unless there's a reason to show. I passed a very pleasant evening last night reading Georgette Heyer. I had picked up The Toll Gate on sale as an ebook, and I might have stayed up a wee bit past my bedtime so I could finish it. It is one of my favorites of hers. She's the mistress of dialogue, and I found myself chuckling out loud at some passages, even though I have read this book several times. She also does a marvelous job of setting a scene without making it feel laborious, as this one:

Swelling with indignation, the waggoner spoke his mind with a fluency and a rang of vocabulary which commanded the Captain's admiration. He then produced the sum of one shilling and tenpence, defiantly mounted the shaft again, and went on his way, feeling that his defeat had been honorable.

The Captain, shutting the gate, found that he was being critically regarded by a buxom woman who was standing outside the toll-house, with a basket on her arm. Her rather plump form was neatly attired in a dress of sober gray, made high to the throat, and unadorned by any ribbons for flounces. Over it she wore a cloak; and under a plan chip hat her pretty brown hair was confined in a starched muslin cap, tied beneath her chin in a stiff bow. She was by no means young, but she was decidedly comely, with well-opened grey eyes, an impertinent nose, and a firm mouth that betokened a good deal of character. Having listened without embarrassment to John's interchange with the waggoner, she said sharply, as he caught sight of her: "Well, young man! Very pretty language to be using in front of females, I must say!" --Georgette Heyer, The Toll Gate